The popularity of wood as a building material is no mystery. It is naturally beautiful, comes in a range of species for almost any application, and is easy to work with.

Because it has all these qualities and more, it is available in a wide variety of sizes and textures. For more information on choosing and buying lumber, as a chart that shows actual sizes of dimension lumber, please see Building Materials Buying Guide.

Lumber Buying Guide

You’re standing at the lumberyard’s checkout counter. The cash register’s numbers spin madly like cherries in a slot machine. You wait with bated breath. Then it happens– the total slams into view. You lose.

It’s tough to win, but the surest way to hedge your losses is to brief yourself before visiting the lumberyard. Know what to look for—lumber types, sizes, and grades—and know how they are sold. Judge your requirements carefully so you don’t buy excessive amounts, inappropriate materials, or unnecessary quality. And, most important, shop around. Make a list of your requirements and call several dealers for the best price.

To help you prepare for your lumberyard experience, here is a basic lumber-buying primer.

Lumber Species and Type

Woods from different trees have varying properties. Notably: redwood and cedar heartwoods (the reddish part of the wood, cut from the tree’s core) have a natural resistance to decay. This, combined with their natural beauty, makes them a favorite for outdoor projects such as patio roofing and decking.

But these woods can be more expensive than ordinary structural woods such as Douglas fir, yellow southern pine, or western larch. For this reason, if used for structural elements or where a painted or stained finish will cover the wood’s natural beauty, redwood and cedar can push the cost unnecessarily high, depending upon the grades you choose.

Many landscape professionals specify Douglas fir and the other structural woods for these parts of an overhead and ensure durability by specifying application of a protective finish.

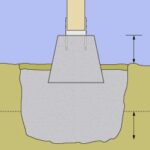

Foundation-grade, pressure-treated lumber is generally the most economical, long-lasting choice for any wood that contacts the ground. It is factory-treated with preservatives that repel rot, insects, and other causes of decay. The American Wood Preserver’s Bureau, which governs this industry, grade-stamps preservative-treated lumber; look for their stamp.

Lumber Grades

At the mill, lumber is sorted by quality grades, then identified with a stamp according to quality, moisture content, grade name, and –in many cases–the species and the grading agency (such as “WWP” for Western Wood Products Association or, in the case of plywood, “APA” for American Plywood Association).

Generally, lumber grading depends on natural growth characteristics–such as knots– on defects resulting from milling errors, and on manufacturing techniques in drying and preserving that affect the strength, durability, or appearance of each piece.

You get what you pay for. In most cases, higher grades are considerably more expensive than lower grades. The fewer the knots and other defects, the more expensive a board or length of dimension lumber. One of the best ways to save money on a project is to pinpoint the right grade (not necessarily the best grade) for each element. The chart below, from the Western Wood Products Association, offers the grade characteristics for boards and dimension lumber.

Lumber Sizes

Anyone who has ever walked through a lumberyard knows that there are many, many different sizes. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll be dividing sizes into these typical categories: lath or battens, up to 3/4-inch thick, boards, about 3/4-inch or 1-inch thick by more than 2 inches wide, and dimension lumber, anything larger.

Lath is sometimes used for open-style roofing. Strictly speaking, common outdoor lath is rough-surfaced redwood or cedar, milled to dimensions of about 3/8-inch by 1 1/2 inches and sold in lengths of 4, 6, and 8 feet, often in bundles of 50. (In a broader sense, the term “lath” can refer to any open-work slat roofing where lengths run parallel, side-by-side.)

For outdoor overheads, be sure to choose high-quality lath, free of excessive knots or other defects. Relatively straight grain is also important, to minimize warping and twisting that can occur under constantly changing weather conditions.

Batten is like overgrown lath, milled in thicknesses of 1/4 to 3/4 inch and widths of 2 to 3 inches. Unlike lath, batten can be purchased in lengths up to 20 feet and is generally sold by the piece rather than the bundle. Although smooth-surfaced batten is sometimes called lattice, it is not sold under this name in all localities. (The term “lattice” also is used to describe a cross-hatch panel.)

Dimension lumber and boards makeup 90% of the lumber stock in a lumberyard. They are the most commonly used materials for posts, beams, rafters, and open-style roofing. You’ll see 1 by 2s, 2 by 4s, 4 by 4s, and other typical sizes of boards and dimension lumber used in patio roofs and gazebos.

The right size to buy. The chart will help you figure the minimum sizes required to support loads when building patio roofs or other outdoor overheads and structures. Keep in mind that these are minimums; you might want to select larger sizes for appearance. In most cases, 4 by 4 posts will carry the needed weight but may look spindly– a 6 by 6 might offer a stronger look. And the larger the beams and joists, the further they can span between posts or supports. Keep in mind that beefier sizes may also beef-up your lumber bill.

Lumber Textures

Milling can produce several different textures. Though surfaced lumber that is smooth is the most familiar, rough or resawn textures are available for a more rustic look.

Surfaced lumber, designated “S4S” (“surfaced on four sides”), is the standard for most construction. You can also buy lumber that has been planed on one, two, or three sides.

Rough lumber, which has been milled to size but not planed smooth, has a splintery surface. Though buying rough lumber can save money, pieces with excessive knots, flat grain, or high moisture content can warp and twist. Rough lumber takes stain but is a poor choice for painting.

Resawn lumber is wood that has been run through a coarse-bladed saw, such as a band saw, to create a scored texture. Though it is not stocked at most lumberyards, landscape professionals often special-order resawn lumber because of its rustic, but not too rough, texture and appearance. It can be very stable—though you will pay a premium for the best selection of boards—and it accepts wood stains easily and beautifully.

Sandblasted lumber is not a milled product, but it has a rustic appearance similar to resawn wood. Sandblasting surfaced lumber is generally not cost-effective unless you are having other sandblasting work to be done, on your siding or pool, for example.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: