Every home has at least one electrical service panel. Some may also have subpanels that serve energy-intense areas of the home, such as a new addition or an upgraded kitchen. Most homeowners know to look at the service panel when they experience a sudden loss of power to see if a breaker has tripped or a fuse has blown. But ideally, you should know more than that. Service panels should be routinely inspected, because certain issues require more than resetting a breaker or replacing a fuse.

Getting to Know Your Service Panel

The service panel’s job is to distribute electricity flowing from a source—in most cases, the electric utility company—to branch circuits within the home. Most branch circuits serve a number of lights and outlets. Sometimes, a single circuit is dedicated to serve a single appliance. This is a code requirement in most locales and good idea when the appliance has a motor (clothes washer, air conditioner or microwave oven) or heating coils (electric range, electric dryer, toaster, clothes iron or blow dryer).

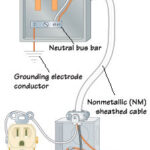

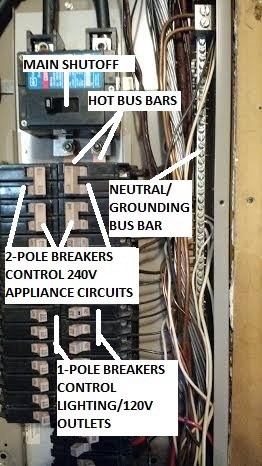

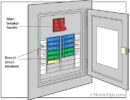

Power purchased from the utility company is fed into the home through a meter at the service entrance. From there, the electricity is routed to the service panel, which is essentially a metal or plastic cabinet installed in or against a wall. Inside the cabinet there are “hot” and “neutral” bus bars—relatively large metal strips designed to conduct substantial amounts of electrical current while dissipating heat—and an array of overcurrent devices, the circuit breakers or fuses. Panels have one “main,” which controls the power supply to the panel, and individual controls for the branch circuits.

The breakers/fuses are rated, in amps, for the safe limit of power that each circuit is designed to serve. They prevent fires by cutting off power when an overload or other fault in the wiring could cause the circuit to overheat.

When a panel is installed correctly, the bus bars and wire connections to the controls are concealed by a cover, which allows only enough access to reset breakers or change fuses. Don’t remove a panel cover unless you are a licensed electrician.

The Evolution of Electrical Service Panels

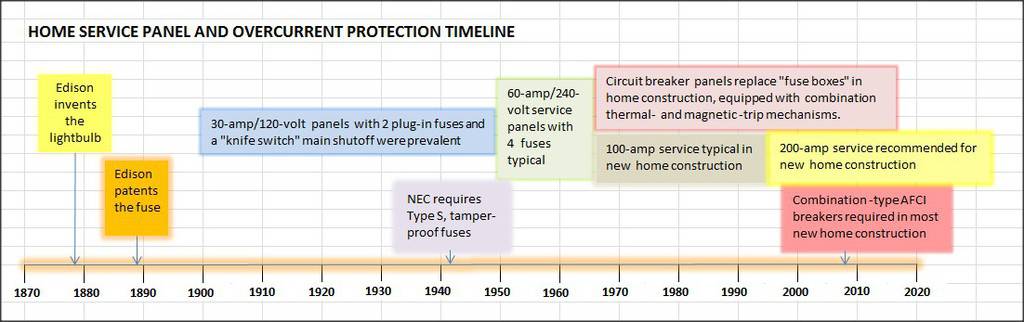

In the beginning, circa 1900, there was the fuse: either a cartridge or a simple glass vial with a metal filament and base that plugged into the service panel. The filament was designed to melt when it got too hot, cutting off power to the circuit. Prior to 1950, most fuse-protected service panels had the capacity to deliver only 120 volts and 30 to 60 amps.

By the 1960s, circuit breakers were introduced and became the norm for houses ever since. The principal advantage of circuit breakers over fuses is that they can simply be reset, rather than needing to be replaced, after responding to a fault. Service panels designed for circuit breakers were designed to deliver 120 and 240 volts with enough breaker mounts for 100-amp capacity or greater. If you are building a house this year, you’d be wise to install a panel with 200-amp capacity.

Some would argue that fuses are more reliable than circuit breakers because they’re less complicated. Standard breakers installed during the era from the ‘60s through the ‘90s incorporate two separate switching mechanisms—a bimetal switch and an electromagnet. The bimetal component trips the switch when it heats up as the result of an overload. The magnetic component breaks the circuit when it senses a short. In a certain sense, circuit breakers are less sensitive than fuses. They’re intentionally designed to disconnect circuits only when heat buildup persists over a period of time.

Research conducted during the mid-1990s led to the development of arc-fault circuit interrupters (AFCIs) that trip when they sense a high-power discharge between two conductors, which can occur, for example, when connections between wires and switch terminals become loose. By 2005, the National Electric Code required combination-type AFCI breakers for all new construction.

Why the History Is Relevant

This history of service panel and overcurrent protection technology is important for two reasons: First, it should keep you from feeling that you have to change out old equipment that’s working properly for new just to keep up. For example, if you have an old house with an electrical system protected by fuses, you don’t necessarily have to replace them with a breaker panel for safety reasons. If you need to add service, have a licensed electrician add what you need with a modern panel, but don’t let him or her talk you into fixing what’s not broken.

The second reason is that if you need to repair or replace components in a service panel, it’s important to know that they must be replaced with parts of the same brand, technology and amperage as the original. If your electrician can’t find compatible components, you might have to start over with a new panel. Knowing when the panel was installed can facilitate that decision.

What Goes Wrong with Panels and Breakers

Electric service panels should be inspected routinely for signs of corrosion. A recent report based on the observations of professional home inspectors asserts that evidence of rust was found on approximately 10 percent of service panels observed—even with the covers in place. If there’s rust on the outside, there’s sure to be corrosion on the inside, which can wreak havoc on connections and damage breakers.

The inspectors found that the source of moisture in panels is usually poor sealing at the service entrance, which should be corrected before the rusty panel is repaired or replaced. Panels in damp, unheated garages and basements are also subject to corrosion.

A breaker can also malfunction and trip more often than necessary. When one or more breakers trip frequently, the cause could be one of three issues:

- The circuit is inadequately designed for the load

- An appliance on the circuit has a fault

- The breaker is worn or otherwise damaged

It’s easy to verify or eliminate the first two potential causes. A circuit overload is the most common problem, which usually becomes obvious when the over-current device controlling it shuts the circuit down only when two or more appliances are in use at the same time—say, the microwave oven and the toaster.

If you suspect that a faulty appliance might be an issue, there a few steps you can take. When a breaker trips, unplug everything on that circuit, then reset the breaker. Plug in one appliance at a time and turn it on. Wait 15 minutes or so. If the breaker doesn’t trip, unplug the appliance and test the next one. If you find the culprit, repair or replace it. You don’t have to worry about the breakers.

If you eliminate both circuit overload and a faulty appliance as the cause for a circuit shutting down frequently, suspect trouble at the panel. Call a licensed electrician to remove the panel cover and perform an inspection. Electricians know how to work safely in an open, energized panel and can diagnose problems through visual inspection and appropriate test procedures.

The electrician will look for evidence of corrosion and overheating inside the cabinet, at terminal connections and on wires themselves. It’s not uncommon to find burnt connections at breakers either because connections weren’t made properly during installation or because they loosened due to excessive vibration. Breakers that are damaged by corrosion and/or overheating can be replaced, as long as the source of the problem is also addressed.

The electrician will also assess whether the current service and system design is adequate for your home’s demand. He or she may recommend a larger panel with more breaker slots to supply more power and/or reduce loads on certain circuits.

Remember that the service panel’s main job is to keep you and your home safe. The best way to ensure that a panel does that job well is to keep a close eye and consult with a qualified electrician to access and correct anything that you find worrisome.

Find an Electrical Pro Near You

Michael Chotiner is a former construction manager who writes about DIY projects for The Home Depot. He provides interesting facts and advice to help you make informed decisions. You can view here a wide selection of breaker panels from The Home Depot.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: