A roundup of the various types of screws, bolts, and nails, and the proper application for each

A variety of nails, screws, bolts, and other fasteners are integral to the construction of houses. Most of these are sold at hardware stores, lumberyards, and home improvement centers; some of the more specialized items are sold at builder’s supply outlets.

Throughout HomeTips, you will see many different types of hardware, some very innovative. In this article, you can gain an understanding of fundamental hardware and fasteners so you can be an informed buyer next time you visit your local hardware store.

Buying Screws

Though they are more expensive than nails, screws offer several advantages for certain types of construction. Screws are stronger than nails, they do not pop out as readily as nails do, and, in most applications, they are easily removed. In addition, their coating is less likely to be damaged during installation, and there are no worries about hammer dents.

Most screws are made of zinc-plated steel, but they also can be made for special purposes from softer metals such as brass and aluminum. Screws also may have finishes that are plain, blued, dipped, brass-plated, or chrome-plated.

Conventional wood screws are measured by length, from 1/4 inch to 6 inches, and the size or gauge of the unthreaded shank, from gauges 2 to 24. They are classified by type of head, each requiring a specific screwdriver tip: standard, Phillips, or square-drive. Before you can drive a screw, you must drill a pilot hole.

Drywall screws (also called multipurpose screws) have a black coating that is not rust-proof; deck screws are galvanized for corrosion-resistance, making them suitable for areas exposed to moisture. Both drywall and deck screws have sharp points, coarse threads along their thin shanks (deck screws have a coarser thread than drywall screws), and Phillips-type heads; they’re designed to be driven with a Phillips screwdriver tip mounted in a power drill or electric screwdriver and generally don’t require pilot holes. Lengths range from 3/4 inch to 4 inches.

Because drywall and deck screws are not rated for strength, use nails, standard screws, lag screws, or bolts when engaging in heavy construction.

Lag Screws, Carriage Bolts, and Machine Bolts

Lag screws, machine bolts, and carriage bolts have many household uses. These fasteners come in larger sizes than wood screws, with shanks ranging from 1/4 inch to 3/4 inch in diameter (in 1/16-inch increments). Most are given a zinc coating for rust-resistance.

Lag screws (also called lag bolts) are heavy-duty fasteners for wood that feature a square or hexagonal head that is driven into wood by a standard wrench or socket wrench and a heavy, partly threaded shank. Before driving a lag bolt, predrill a pilot hole about two-thirds the bolt’s length using a drill bit that is 1/8 inch smaller than the lag bolt’s shank. Slide a washer onto the lag bolt before driving it in.

Carriage bolts have a rounded head that grips into wood from its underside when the nut is tightened with a wrench. Before driving a carriage bolt, drill a hole that’s a snug fit for the threaded shaft, and drive the bolt into the wood with a hammer.

Machine bolts are for fastening together wood or metal—washes go under both the head and the nut and they’re tightened with a standard wrench or socket wrench. Before driving a machine bolt, drill a pilot hole that’s the same size as the bolt’s shank.

Buying Nails

Nails are classified by shank size and type and by the shape of the head. Most nails are made of steel, but you can also buy stainless-steel, bronze, and aluminum nails for specialty tasks. Hot-dipped galvanized nails, coated with zinc, are rust-resistant and meant for use outdoors where they may be exposed to moisture.

Common nails, used for rough construction, have an extra-thick shank and a broad head. Drywall nails, a variation, have a thinner shank and a larger, slightly cupped head; annular-ring nails, best used for installing drywall on ceilings, have a ribbed shank that grips better.

Finishing nails are for where you don’t want a nailhead to show. (After you drive the nail nearly flush, sink the slightly rounded head below the surface with a nailset.)

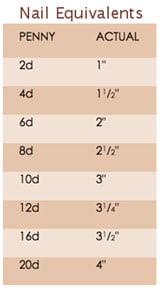

Nails, sold by the pound or in 1-, 5-, and 50-pound boxes, come in different styles and sizes. Nail lengths may be designated by inches, but the term “penny,” abbreviated as “d,” is more common. This term is a carryover from long ago when it specified the price for a hundred hand-forged nails.

Hollow Wall Fasteners

When fastening heavy objects to walls or ceilings, it is ideal to screw through the wall covering into the wall studs or ceiling joists that back the material. Where this isn’t possible—between framing members, for instance—wall fasteners can be used. Masonry walls also call for a fastener or anchor that will expand into a drilled hole.

An expanding anchor bolt is inserted into a hole drilled into solid masonry. As the nut is tightened, the anchor expands and cannot be removed. A lead shield, inserted in a hole drilled in masonry, receives a screw or bolt that, when tightened, causes the shield to expand in the hole.

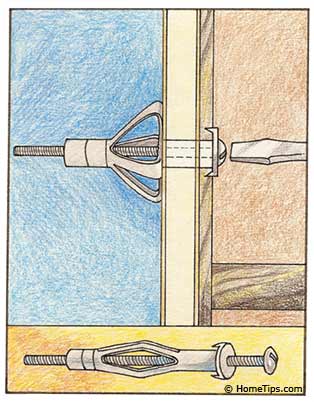

A spreading hollow wall fastener has a sleeve that opens like an umbrella when a bolt is driven into it. Once installed, the bolt can be removed but the anchor is permanent.

A toggle bolt (“molly bolt”) is a two-part fixture consisting of a bolt and spring-loaded “toggle wings” that pop open on the backside of the wall material, providing a sound anchor for tightening the bolt—this fastener is particularly strong. You insert it through a hole that’s big enough to receive the spring-loaded wings when they’re pinched shut, then pull the opened wings against the backside of the wall was you screw-in the bolt. These are tricky to use—you have to assemble the object you’re hanging onto the bolt before pushing the toggle bolt into the hole. Note: If you unscrew the bolt all of the way, the toggle falls into the wall.

Drive-in hollow-wall fasteners. These strong hollow-wall fasteners are a dream to use. You just decide where you want to screw something to the wall and drive the heavily-threaded base into the wall, using a power drill with a Phillips screwdriver tip. The base then receives the screw, which comes with it in the package. Lightweight versions are made of plastic, while heavy-duty anchors are made of metal.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: